Give and Take: A Nurse’s Role in Organ Transplantation

For the past 20 years, registration for organ donations has steadily increased in the United States — but not quickly enough to match the number of people in need of transplants. The wait for organ transplantation claims the lives of 20 Americans every 24 hours. And the size of the waitlist continues to grow, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

Support for organ donation is high — almost 95 percent of Americans are in favor — yet only half of adults in the U.S. are officially registered. Why is that? There are many barriers to entry for people who are considering organ donation, including registration requirements, moral and ethical conflicts, and contradictory information about the donation process, much of which can be addressed by Nurse Practitioners (NPs) through patient education.

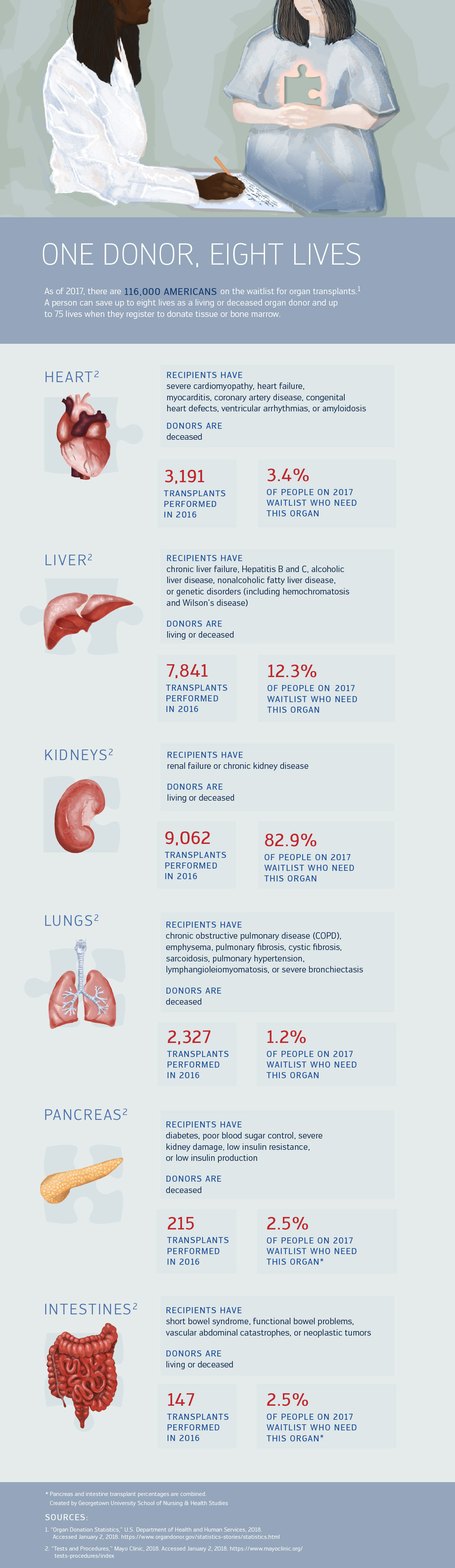

A single donor can help 75-plus people through “organ, eye and tissue” donation, according to Donate Life America.

The graphic below illustrates the eight types of organs one person can donate, and how often those organs are requested by patients.

View the text-only version of this graphic.

Becoming a Donor

Organ transplantation is the process of moving a viable organ from a donor to a recipient, and depending on the organ, it can happen while donors are alive or deceased. Organs from deceased donors can only be harvested after brain death or cardiac death. In the case of brain death, a patient experiences an irreversible absence of brain function after a trauma, stroke, aneurysm, or developing a brain tumor. A cardiac death occurs when the respiratory and circulatory systems no longer work and can happen after a patient experiences cardiac arrest, heart disease, or other heart problems.

Donors can register online, at the DMV, or through their voter registration cards, depending on the state. Registration serves as a person’s legal consent to donate an organ, which must be followed by a medical evaluation to determine that a person’s organs are healthy enough to be transferred to a patient in need.

It’s important for donors to make their wishes known to family members, caregivers, and medical providers so they can act accordingly in the event of death or the transfer of a patient’s medical power of attorney.

Navigating Conflict

In the best case scenario, organ recipients have a nurse dedicated solely to their care, in addition to a multispecialty team. Transplant nurses support the patient and their family members before, during, and after the transplantation surgery, providing fluid and blood replacement while monitoring for complications.

Nevertheless, the organ donation process remains complicated, as patients become desperate to find a match or struggle to navigate recovery in their life after transplantation. With multiple parties involved, patients and their families often look to a single medical point of contact to offer guidance in these complicated situations. Nurses often serve as this resource.

The American Nurse Association’s Code of Ethics is a guide for such nurses. Of the nine provisions, a few are especially applicable for NPs caring for donors or recipients of transplants:

- “The nurse practices with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person.

- The nurse’s primary commitment is to the patient, whether an individual, family, group, community, or population.

- The nurse promotes, advocates for, and protects the rights, health, and safety of the patient.”

Supporting Patients through Education

Many transplant patients are receiving or donating an organ for the first time, meaning they are less aware of the lifelong implications of the operation. The best way for Nurse Practitioners to help patients make their decisions is to provide them with all the facts regarding the transplantation process.

Nurse Practitioners can educate the patient on the operation process and risks of complications, and they can answer the family’s questions. A common misconception about organ transplantation is the amount of time and resources involved in recovery. Many patients are required to follow up each week, adhere to specific diets, visit clinics for blood work, or plan for other long-term lifestyle changes.

It is critical to discuss outpatient treatment thoroughly so that patients aren’t surprised when it comes time to discharge, according to Allie Hayes, a Nursing@Georgetown student and transplant nurse at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital.

“Some patients can’t eat sushi for a year after their operation, and that’s always a shock,” Hayes said. “It’s the little details that make people realize that a transplant really does affect the rest of their lives.”

NPs must always put the patient’s well-being first, meaning they often become a patient’s advocate when patients can’t speak for themselves. “Georgetown really cares about cura personalis,” said Hayes, referring the curriculum’s focus on each person’s needs. “Of course, the physical body is looked after by everyone on the care team, but the attention for the mind and spirit is really left up to the nurses.”

Ethical Considerations

Sometimes care teams will call a third party for an ethical consult, but most NPs become accustomed to navigating ethical quandaries while supporting patients, especially since they spend the most time with them and their families.

Though NPs are tasked with many roles in the transplant process, patient coercion is not one of them. Sometimes people will feel obligated or pressured to get tested to see if they are a match to an ill family member, but that conversation is held with the transplant evaluation team. “The evaluation team works to maintain patient confidentiality and ensure that the transplant is desirable for the patient and the donor,” said Hayes.

According to Hayes and Carol Taylor, RN, PhD, professor at Georgetown University School of Nursing & Health Studies, there are many ethical questions every NP should consider, several of which are critically important:

Is the donor’s death being hastened?

Organ procurement should never be the reason that a patient dies; the circumstances surrounding a patient’s death should be considered independently of whether the person is an organ donor or match. “It’s primarily a rescue culture though,” Taylor said of organ transplantation, meaning medical professionals in the transplantation field are inclined to act quickly, but they should always be putting the patient’s wishes and well-being first.

How well-informed is the consenting patient?

Nurses must cosign a consent form stating that the patient was educated on the risks of the procedure and, more importantly, that the patient fully understood those risks before agreeing to receive an organ. Hayes emphasized taking extra time to debrief the patient and answer any questions before signing. “I use the teach-back method, where the patient explains to me what they understand, and then we go over any new questions that come up,” she said.

Does the patient have a support system?

Every transplant patient — donor or recipient — must be discharged with at least one caretaker, sometimes more, if the patient has specific needs or disabilities. “This is supposed to happen during pre-screening for patients, but sometimes it’s overlooked,” Hayes said. During the transplantation, NPs provide support and advocacy for patient needs, but it’s critical for a patient to have a community that provides care long after discharge.

What are the motivations behind donation?

Relationships between donors and recipients can be complicated; it’s important to discuss the reasons why a person is or isn’t willing to donate. Expectations of reward, obligation, and fear of losing a family member can play heavily into a patient’s motivations and should be discussed confidentially with a medical provider during the pre-screening process. By advocating for patients, nurses help them to maintain their self-determination over their life. The nurse should fully understand their patients’ wishes in the event of death and must grasp how their patients intend to add meaning to their death if they choose to donate their organs.

“They’re putting their lives in your hands,” Taylor said. “You have to deserve that.”

Saving More Lives

To find more information about donor registration, awareness, or volunteer opportunities, visit www.organdonor.gov.

Please note that this post is for informational purposes only. Individuals should consult their health care professionals before following any of the information provided. Nursing@Georgetown does not endorse any organizations or websites contained in this post.

Citation for this content: Nursing@Georgetown’s Online FNP Program