Back to School: Patient Education

A single hospital stay can be filled with an overwhelming amount of new and sometimes unfamiliar information for a patient. In fact, almost all patients forget at least one medication prescribed to them during a stay in a hospital, hurting their likelihood of fully adhering to their care plan once they are discharged.

How to take medication as prescribed is just one of the many things clinicians teach patients. Communicating pertinent information about a prognosis or recommending lifestyle changes poses meaningful challenges in health care, especially when patients remember more about their initial diagnosis than the steps they’ll need to take to get back on the right path.

Frontline clinicians often serve as patients’ teachers, and in many ways they share some of the setbacks and achievements teachers face in the classroom. Learner success relies on motivation, specificity, and a thoroughness that guarantees the highest level of understanding possible.

But in health care, lessons must also be actionable because they have lifelong implications for health outcomes. Educators must balance keeping complex content both understandable and accurate, often with limited time.

Georgetown University School of Nursing & Health Studies adjunct professor Nicole Martinez, MSN, APRN, FNP-BC, PHN, transitions from teaching patients to teaching students—and back again—in her professional roles. She said in both contexts, educators serve a supportive purpose.

“We’re not just here to do a job. In both [academia and nursing], we’re here to communicate and to take care of patients and students,” she said. “You can’t ignore or forget that personal aspect.”

Clinicians as Teachers

Experts believe patient education is most successful when it is continuous and when every interaction between clinicians and patients is either an assessment of needs, actual teaching, or an evaluation of understanding.

When surveyed, patients opt for Nurse Practitioners because of the consistency of those interactions. They say nurses listen to, spend time with, and give feedback to patients in a way that is helpful.

The ongoing conversations nurses have with patients allow them to discover the best ways to relay information based on things like a patient’s motivation and learning style.

Martinez said a patient’s learning style should guide all interactions moving forward. Will the patient respond better to a conversation or visual aids? Would they prefer to read about their diagnosis or take notes?

“[Nurses] explore that from the minute we come in contact with the patient. How do you learn? We try to learn how they best receive information in order to help them reach their health goals,” Martinez said.

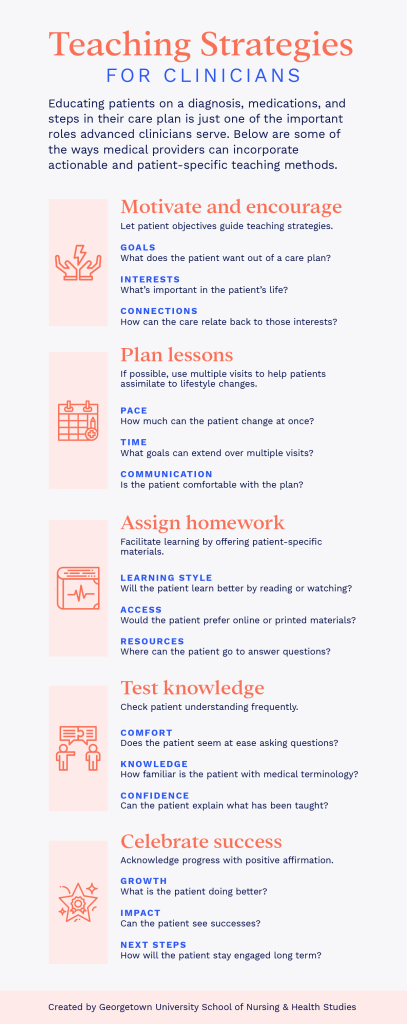

View text-only of infographic.

Strategies from the Classroom

Utilizing different learning styles is just one of the ways nurses can be effective teachers for their patients. With a projected potential shortage of 120,000 physicians in the next decade, the opportunity to address patient questions, concerns, and needs will increasingly be led by nurses. What other strategies can they use that translate from the classroom to the bedside?

Motivate and Encourage

Engagement is a powerful tool in education, so much so that it can help students overcome struggles with understanding course content. A study of academics and a Nobel laureate with dyslexia found that study participants were able to overcome their reading challenges because of their deep interest in the subject matter.

The same is true for patients: Structured, patient-specific materials are most successful in changing behavior.

Relate content back to what the patient values most. Why are they in your care? What is their goal? How will your teaching help them reach that goal?

For example, a patient trying to quit smoking is motivated by more than just the act of smoking. Maybe he wants to stop coughing so he can breathe more easily, or perhaps he is facing pressure from family members. Motivate patients through those interests as opposed to concepts of health with which they may not identify.

Plan Lessons

Learning something new over time is more effective than absorbing the same information in one sitting. Research recommends that students study material in shifts of about an hour with breaks in between.

For patients, “course material” often amounts to lifestyle or behavioral changes that can take longer to learn and adapt into everyday practice. Studies show it can take an average of two months for people to develop a habit and even longer for more complex changes.

Martinez recommends building on previous information with each visit. Instead of presenting everything at once and expecting compliance, reintroduce information over time as the patient assimilates to lifestyle changes.

Assign Homework

In short-term settings like hospitals and outpatient care, clinicians must work within the limited time they have with patients. When this is the case, treat patient interactions like a single course. Martinez recommends that clinicians engage with patients right away in those cases.

“You can immediately develop a rapport if you listen,” she said. “Everything else moves a lot more smoothly because you have their attention and you have their trust.”

Give patients the appropriate tools to continue to learn and improve after they no longer are in a clinician’s care. Older patients, for example, exhibit better health when they have continued access to multiple resources and aggregated health care information.

Test Knowledge

Evaluate the patient’s knowledge of material frequently. While written exams are not appropriate for the bedside, clinicians may use other methods to check for understanding.

Use the teach-back method for a more direct approach, and ask patients to explain, in their own words, the instructions or material taught to them. Ask questions of patients, and show a genuine interest in their learning.

Asking questions can also help clinicians better understand patients’ comfort with medical terms, and in turn make it easier to educate them on the appropriate level—a place where they understand and feel empowered.

Look for nonverbal cues that indicate confusion or doubt. Martinez said this can be as obvious as the “deer in the headlights” look. When she sees that, she knows she needs to follow up further, like in the case of a patient who just heard about a large mass in her brain.

“I looked at her and I put my hand on her hand … and I said, ‘That was a lot to take in and I want to make sure that you understand what’s going on,’ ” Martinez said. “And the patient just broke down crying. She said, ‘I stopped listening to him when he said you have a mass in your brain.’ And I could see that when he was talking to her.”

That’s when Martinez knew she had to pivot and reiterate to the patient what she needed to know in a way that she could hear and respond to.

Celebrate Success

The nature of health care means patients often receive feedback in terms of what is wrong and what should be done differently. Calling attention to needed change is important, but celebrating successes along the way can be powerful as well.

Students are more likely to continue their education when they receive encouragement. In the same way that teachers offer feedback throughout the semester, enthusiasm and reinforcement have the same effect with patients and let them know they are taking the appropriate steps with their health.

“Patients need validation, just like anyone,” Martinez said. “It’s nice to have someone in your corner, and I think that both patients and students long for that.”

Martinez said providing that assurance is a teaching strategy that translates beyond her roles in the classroom and at the bedside.

“I think more patients and students need to know that there is someone who is proud of them for doing what they’re doing. It’s a very innate human need for each of us to have that type of connection.”

Citation for this content: Nursing@Georgetown, the online MSN program from the School of Nursing & Health Studies