How to Talk About Cancer: A Communication Guide for Cancer Patients, Providers, and Loved Ones

There is no one right way to share a cancer diagnosis, and loved ones of cancer patients will often have different reactions to the news. Although cancer patients do not have to share information about their condition with everyone in their lives, preparing to have difficult conversations can help ease tension around talks about a cancer diagnosis, treatment, and outlook.

Nurses, too, can learn strategies for gentle and effective communication with cancer patients.

Read on to learn more about how nurses, patients, family, and friends can effectively communicate about cancer. The links below can help you navigate to sections that offer communication tips based on your relationship to a cancer patient.

Table of Contents

How Nurses Can Discuss a Cancer Diagnosis, Treatment, and Progress With Patients

Because nurses often spend more time with cancer patients than most other members of their care teams, nurses are well positioned to communicate with these patients in their most vulnerable moments.

“The nurse really does end up kind of being this person that the patient feels most connected to,” said oncology nurse Amanda Hartwell, RN, BSN. “When it comes to communicating, even if we’re not the ones giving the bad news, we often come in the room afterward and kind of are the ones that are helping them work through that news.”

The National Cancer Institute echoed her sentiment: “Nurses are frequently the most trusted member of the cancer team when it comes to obtaining information, and they serve as advocates for the patient when important and sensitive questions such as ‘How bad is it?’ or ‘How long do I have to live?’ arise.”

During inpatient stays, nurses act as advocates and translators for patients, particularly after brief interactions with physicians and other providers.

“A lot of times the patients are just very overwhelmed, and it’s too much information for them all at once, and so the nurse is really the advocate. They are interpreting the information in a way that the patient and the family can understand,” said Hartwell, a student in Georgetown University’s Online FNP Program.

And in outpatient settings, communication is a nurse’s biggest role, Hartwell said. Outpatient oncology nurses must develop a rapport with patients and families so they become a reliable point of contact within the care team.

“That nurse is really the first point of contact for the patient in any way that they’re communicating,” she said.

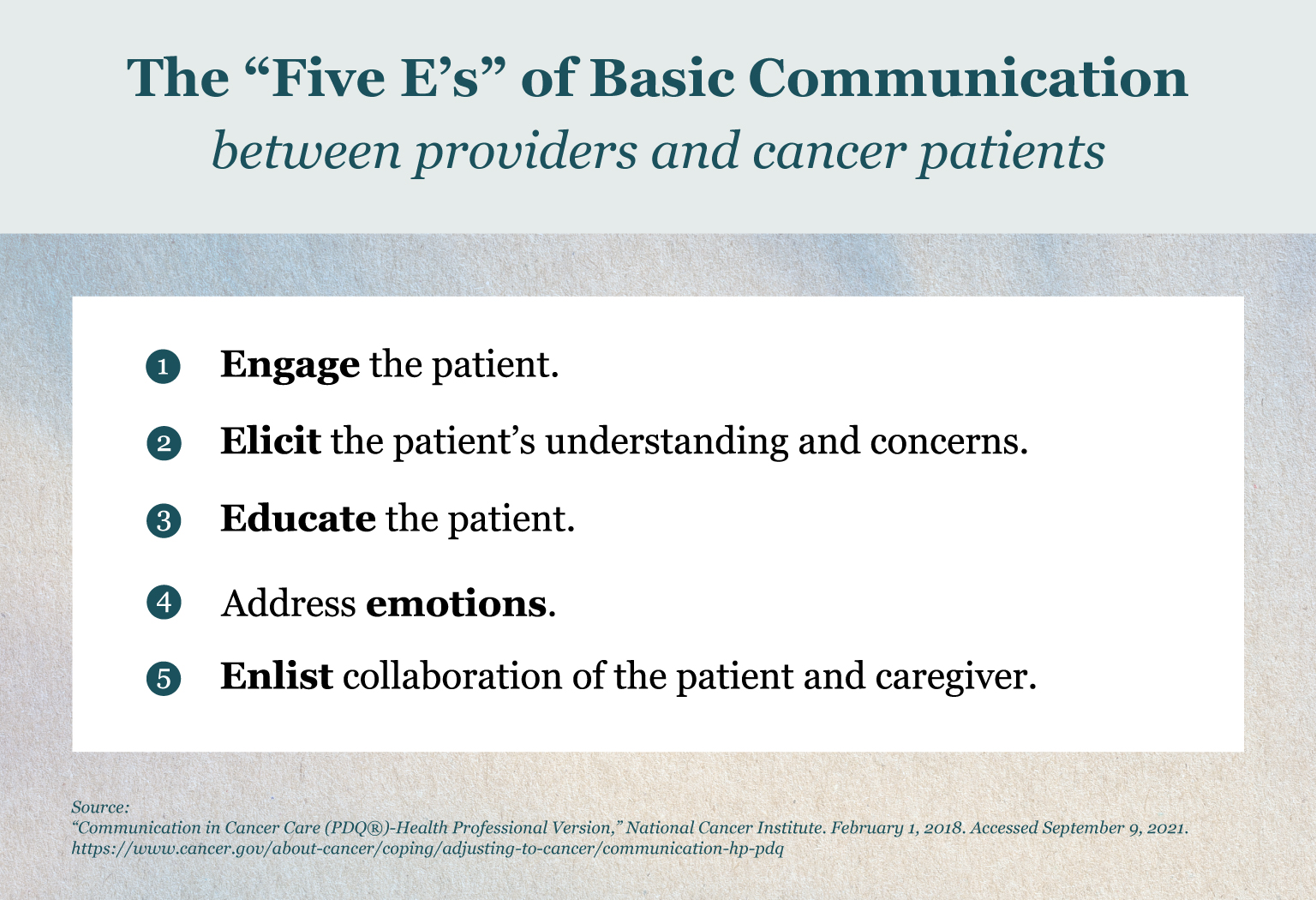

Nurses can use “the five E’s” of basic communication as a starting point for interacting with oncology patients.

The five E’s of basic communication help health care providers establish a rapport with patients, explain a patient’s condition, provide information about the illness and treatment, respond to emotions with empathy, and involve the patient’s family in their care plan.

When having difficult conversations, it helps to meet a patient where they are and ask what level of information they wish to receive, Hartwell said.

“I usually start my difficult conversations with patients by first letting them know I’m about to share some information that might be difficult. That gives the patient and their family kind of a heads-up to prepare themselves that they’re about to receive some bad news,” Hartwell said.

“I usually try to follow that up by saying, ‘How much detail would you like? Do you want the synopsis version? Do you want to know everything?’ And that can help really make sure that we’re not overloading them.”

Making space for silence is another strategy nurses can employ during tough exchanges with patients.

“We’re always worried about our response, but in reality, a lot of patients respond better to just you sitting there and listening to them, giving them a tissue if they need it, leaving the room if they want, a hand on their shoulder,” Hartwell said.

“The technique of being able to just sit back and letting them process the information you’re giving cannot be overstated.”

How Nurses Can Communicate With Adult Cancer Patients

These strategies may help nurses deliver information to patients about cancer treatment and prognosis:

- Take a patient-centered approach to communication.

- Patients vary in how much information they want to know about their condition, so ask patients how much information they want to know about their prognosis and progress before sharing that information.

- Involve the patient’s family in communication about treatment goals, care plans, and expected outcomes.

- Be attentive, interested, and friendly to help improve patient satisfaction.

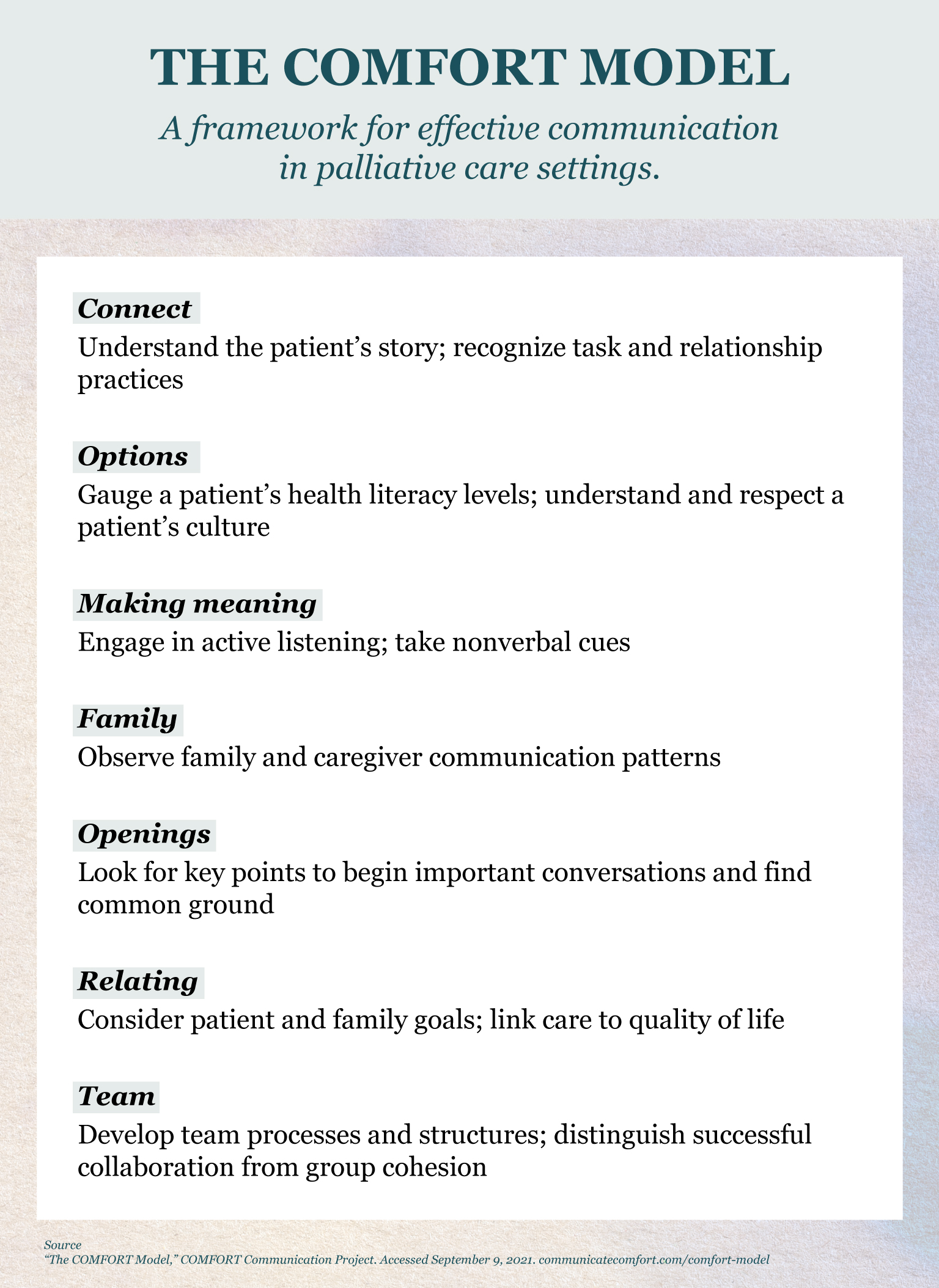

- Use the COMFORT model, which offers seven principles for palliative care communication.

COMFORT is an acronym for seven principles that assist in palliative care communication. Health care providers can seek online training through the COMFORT Communication Project to develop stronger communication habits in these areas.

Sources:

- “Communication in Cancer Care (PDQ®)-Health Professional Version,” National Cancer Institute. February 1, 2018. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/coping/adjusting-to-cancer/communication-hp-pdq

- “The COMFORT Model,” COMFORT Communication Project. Accessed September 9, 2021. communicatecomfort.com/comfort-model

- Wittenberg, Elaine, Anne Reb, and Elisa Kanter. “Communicating with Patients and Families Around Difficult Topics in Cancer Care Using the COMFORT Communication Curriculum,” Seminars in Oncology Nursing. August 9, 2018. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6156926/

How Nurses Can Talk to Pediatric Patients and Their Families About Cancer

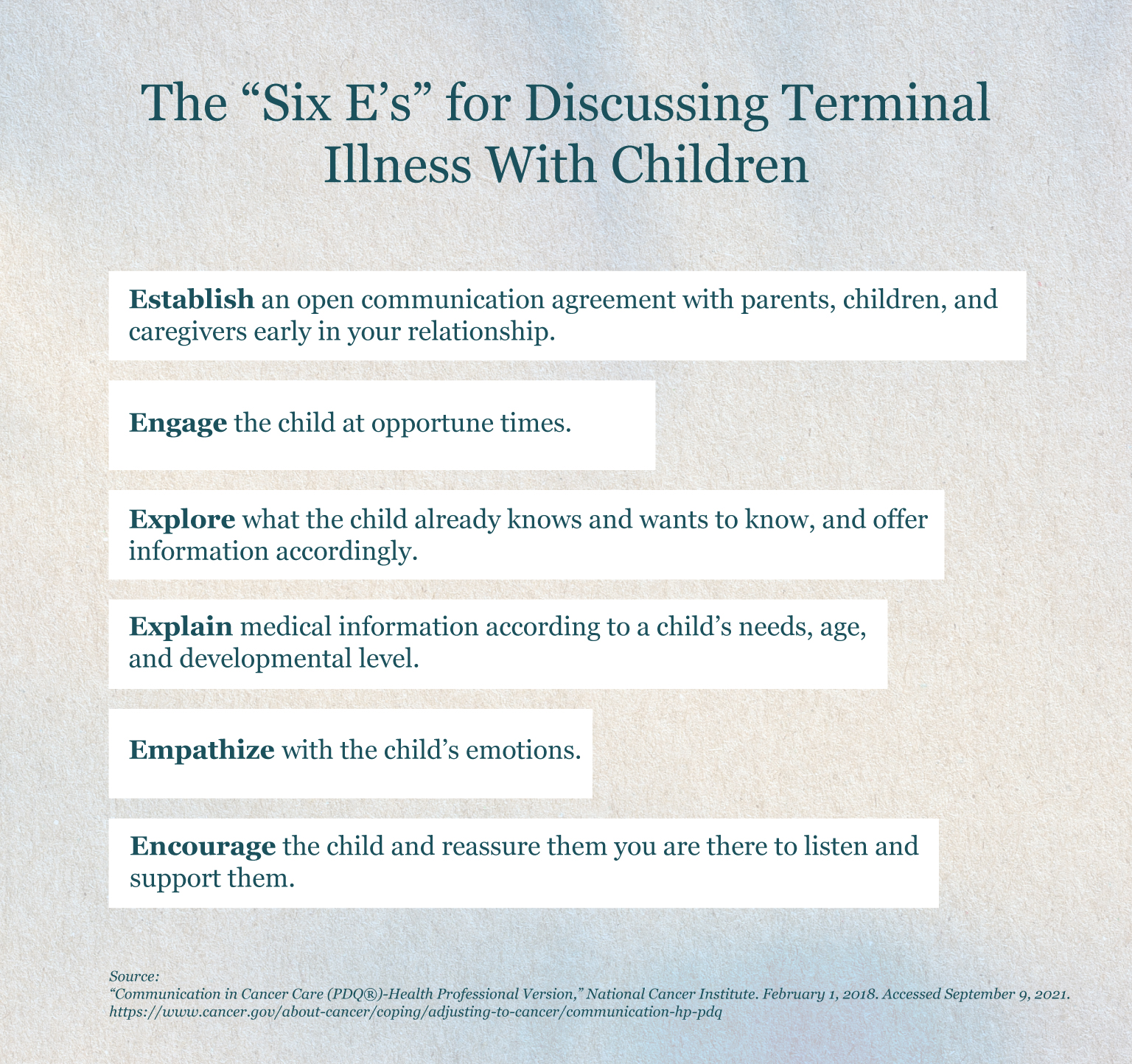

Strategies known as the “Six E’s” can help nurses and other health care providers communicate with children with terminal illnesses.

The “Six E’s” are guidelines for pediatric health care providers to engage with young patients with terminal illnesses and their families.

In addition to the tips above, these techniques may help nurses engage with pediatric cancer patients:

Forge a plan with parents to involve children in medical conversations, and discuss the diagnosis with the child early in the disease course.

Establish a therapeutic alliance with the patient, family members, and caregivers by inviting them to be part of the medical team, asking about their needs and preferences, educating them about the diagnosis and treatment, empathizing with their frustrations, and meeting regularly.

Have several conversations with families about the prognosis over time to empower them to make decisions that align with their care goals.

Support pediatric patients in taking control of appropriate aspects of their care.

Convey a sense of hope — an essential part of the patient journey — balanced with realism.

Sources:

- “Communication in Cancer Care (PDQ®)-Health Professional Version,” National Cancer Institute. February 1, 2018. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/coping/adjusting-to-cancer/communication-hp-pdq

- Blazin, Lindsay, Cherilyn Cecchini, Catherine Habashy Erica C. Kaye, and Justin N. Baker. “Communicating Effectively in Pediatric Cancer Care: Translating Evidence Into Practice,” Children. March 11, 2018. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5867499/

How Cancer Patients Can Share Information About Their Condition

Having conversations around your personal cancer diagnosis, treatment, and progress can be delicate. Hartwell always suggests to patients that they do not owe it to anyone to disclose information about their cancer journey.

“This is their story. This is their diagnosis. This is their life, and they should thoughtfully consider that when they think about telling people,” Hartwell said. “Nobody else has any right to know anything.”

The tips below may help cancer patients of different ages take control of conversations about cancer and share information about their condition with their children, friends, and peers.

How Parents Can Talk to Their Children About Cancer

Be open and honest with your children about your diagnosis rather than keeping it a secret.

Pick a quiet, calm time to talk with your kids about your condition. It may be helpful for two-parent families to tell their children together. Families with multiple children should consider the ages and development levels of their children to determine whether it makes more sense to have one-on-one conversations or talk with them as a group.

Use appropriate language for your child’s age and development level. Share fewer details with children under age 8 and more details with children ages 8 to 12 and teenagers.

Share the basics about your diagnosis, including the type of cancer, where it is in your body, what will happen with treatment, and how their lives might change as a result.

Anticipate children’s questions, and prepare to answer them. Rehearse how you will respond if a child asks whether you’re going to die.

Explain that no one is at fault. Children tend to blame themselves for things that happen to their loved ones, so address the fact that developing cancer is no one’s fault and that the disease is not contagious.

Reassure your child that they will always be cared for.

Check in with your children throughout your cancer journey to gauge how they are feeling about it.

Sources:

- “Helping Children When a Family Member Has Cancer: Dealing With Diagnosis,” American Cancer Society. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.cancer.org/treatment/children-and-cancer/when-a-family-member-has-cancer/dealing-with-diagnosis.html

- “How to Tell a Child That a Parent Has Cancer,” American Cancer Society. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.cancer.org/treatment/children-and-cancer/when-a-family-member-has-cancer/dealing-with-diagnosis/how-to-tell-children.html

- “What If My Child Asks If I’m Going to Die?” American Cancer Society. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.cancer.org/treatment/children-and-cancer/when-a-family-member-has-cancer/dealing-with-diagnosis/asks-going-to-die.html

- “What Do Children Need to Know About the Cancer Treatment?” American Cancer Society. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.cancer.org/treatment/children-and-cancer/when-a-family-member-has-cancer/dealing-with-treatment/need-to-know.html

- “Talking With Family, Friends and Children,” Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.lls.org/managing-your-cancer/do-i-tell-anyone-i-have-cancer/talking-family-friends-and-children

How Adults Can Share Information About Their Cancer

Decide who to share information with and how you will do it.

There is no right way to share information about your cancer, and you do not have to disclose that information with anyone you do not want to. However, sharing how you’re feeling with those closest to you may help alleviate the emotional burden that comes with cancer. Consider the ramifications of sharing your cancer story on social media. And think about telling your employer if you will need time off work for treatments or to determine if you are eligible for the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA).

Take steps to mitigate feelings of being overwhelmed if talking about your diagnosis and treatment becomes hard to handle.

Set boundaries when you do not want to talk about your condition. Learn your trigger points to understand what information is too sensitive to discuss, and plan how you will respond. If you do not wish to disclose information about your condition with someone, refer them to the American Cancer Society or other organizations where they can learn more. Using platforms like CaringBridge can keep followers updated on your condition and progress without having to share that information in multiple settings. And a friend or family member appointed as a spokesperson can help share information with others when you cannot.

Ask how your friends and family are feeling about your condition.

Although their experience will be different, your loved ones may also struggle with your cancer diagnosis and progress. If they want to talk about it, do not ignore them when they need to talk, or schedule a time to have a conversation. When people ask how they can help, offer specific requests.

Be honest with yourself and others about how you are feeling.

Honor your feelings, and do not put on a “happy face” on days when you’re feeling physically or emotionally drained. Do not ignore your need to talk to someone else about your physical and mental health. If speaking with your loved ones is too difficult, seek counseling or try finding a support group for a more anonymous setting. Social workers at cancer centers can also support cancer patients in processing how to share information.

Sources:

- “Telling Others About Your Cancer,” American Cancer Society. April 28, 2016. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.cancer.org/treatment/understanding-your-diagnosis/telling-others-about-your-cancer.html

- Mapes, Diane. “‘Coming Out’ With Cancer: Patients, Experts Discuss Ins and Outs of Sharing a Diagnosis,” Fred Hutch. January 8, 2016. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.fredhutch.org/en/news/center-news/2016/01/coming-out-with-cancer-disclosing-diagnosis.html

- “Tips for Talking With Your Employer and Your Workplace Rights,” Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.lls.org/managing-your-cancer/do-i-tell-anyone-i-have-cancer/tips-talking-your-employer-and-your-workplace

How Teens Can Tell Their Friends About a Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment

- If you choose to disclose your diagnosis to friends, consider the easiest medium to tell them, whether it’s in an email, a phone call, or a face-to-face chat. Alternatively, you could appoint one close friend to share the news with others.

- Your friends may be scared to talk to you about your cancer, so don’t be afraid to bring it up.

- Give your friends the facts about your cancer and treatment, and reassure them that, through it all, you’re still the same person.

- Tell your friends how you would like them to support you, such as asking them to keep calling you even if you do not always want to talk or asking them to visit you at the hospital.

- Your friends may also worry about bothering you, so don’t hesitate to reach out to them to stay in contact if they find it difficult to stay in touch.

Sources:

- “Talking to Your Friends About Cancer,” AboutKidsHealth. September 3, 2019. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://teens.aboutkidshealth.ca/article?contentid=3508&language=English

- “Friends,” Youth Cancer Service/Canteen. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.canteen.org.au/youth-cancer/treatment/relationships/friends/

- “Cancer and Friendships,” Cancer.Net. June 2019. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/young-adults-and-teenagers/cancer-and-relationships/cancer-and-friendships

How to Respond to a Friend’s Cancer Diagnosis

When loved ones learn of a friend or family member’s diagnosis, talking about cancer can be tough. Hartwell encourages friends and family members to offer words of support and suggest specific ways of helping.

“Instead of asking, ‘What can I do for you?’, ask, ‘Can I bring you a meal for dinner tonight?’ or, ‘Can I bring you some lotions you can use after chemo?’ Offer specific things so that the patient can just say yes or no,” she said.

The ideas below — for teens and adults — can help friends and family thoughtfully approach loved ones who have cancer.

Do’s and Don’ts: Tips for Teens Supporting Friends Who Have Cancer

Do check in and ask how your friend is doing.

Don’t always wait for your friend to bring up their cancer.

Do talk about some normal things.

Don’t always focus on cancer.

Do affirm your friend’s feelings.

Don’t change the subject when it becomes uncomfortable.

Do use humor when appropriate.

Don’t joke about your friend’s changing appearance.

Do be open about how you’re feeling.

Don’t hide your feelings about your friend’s condition.

Do check in and ask how your friend is doing.

Don’t always wait for your friend to bring up their cancer.

What to Say to Someone With Cancer: General Tips for Communicating With Cancer Patients

Avoid

Interjecting with unsolicited advice and questions.

Telling the patient how to feel or trying to move past discomfort.

Always being solemn and serious.

Always talking about cancer.

Meeting your loved one’s treatment decisions with judgment.

Asking “How are you?”

Saying “You look great!”

Putting forth empty offers to help.

Only offering support during a loved one’s treatment.

Instead

Ask permission before offering ideas or addressing sensitive subjects.

Acknowledge their emotions and create space for sadness and other uncomfortable feelings.

Use humor and laughter to lighten the mood.

Try talking about other “normal” topics.

Support their chosen course of treatment.

Try saying “I’d like to bring you a moment of joy. What would you like to do right now?”

Try saying “It’s great to see you.”

Ask for specific ways you can make your loved one’s life easier and be sure to follow through.

Consider how their needs might change after treatment, too.

Sources:

- “Supporting a Friend Who Has Cancer,” Cancer.Net. April 2018. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.cancer.net/coping-with-cancer/talking-with-family-and-friends/supporting-friend-who-has-cancer

- Grayzel, Eva. “What You Can Say to Someone With Cancer During and After Treatment,” Cancer.Net. July 16, 2019. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.cancer.net/blog/2019-07/what-you-can-say-someone-with-cancer-during-and-after-treatment

- “Talking With Someone Who Has Cancer,” Cancer.Net. May 2019. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.cancer.net/coping-with-cancer/talking-with-family-and-friends/talking-about-cancer/talking-with-someone-who-has-cancer

- Brody, Jane E. “What to Say to Someone With Cancer,” The New York Times. January 13, 2020. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/13/well/live/what-to-say-to-someone-with-cancer.html

What Not to Say to Someone With Cancer

Some ideas are not helpful when speaking with people who have cancer. The following phrases and sentiments should be avoided in conversations with cancer patients.

“I know how you feel.”

“Don’t worry, you’ll be fine.”

“It could be worse.”

“Everything happens for a reason.”

“How long do you have?”

“At least you’re alive.”

“Is there a cure?”

Sources:

- “Wait… Did You Say ‘Cancer’? A Guide to Supporting Your Friend When They Have Cancer,” Canteen. 2013. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.canteen.org.au/resource/a-guide-to-supporting-your-friend-when-they-have-cancer/

- “Supporting a Friend Who Has Cancer,” Cancer.Net. April 2018. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.cancer.net/coping-with-cancer/talking-with-family-and-friends/supporting-friend-who-has-cancer

- “What Can I Say to a Newly Diagnosed Loved One?,” CancerCare. April 28, 2020. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.cancercare.org/publications/104-what_can_i_say_to_a_newly_diagnosed_loved_one

Additional Resources

These resources provide more information about how to communicate regarding cancer:

- American Cancer Society: Treatment & Support

- American Cancer Society: Words to Describe Cancer and Its Treatment

- Cancer Support Community

- CancerCare: Publications

- Georgetown University School of Nursing & Health Studies: Managing Mental Health After a Cancer Diagnosis

- Leukemia & Lymphoma Society: Do I Tell Anyone I Have Cancer?

- National Cancer Institute: Communication in Cancer Care (PDQ ®)-Patient Version

- National Cancer Institute: Talking to Children About Your Cancer

- The National Children’s Cancer Society: An Educational Guide for Friends of Teens With Cancer (PDF, 1MB)

Please note that this article is for informational purposes only. Individuals should consult their health care provider before following any of the information provided.

Citation for this content: Nursing@Georgetown, the online MSN program from the School of Nursing & Health Studies