Shaping Cities to Support Health: A Closer Look at Global Urbanization

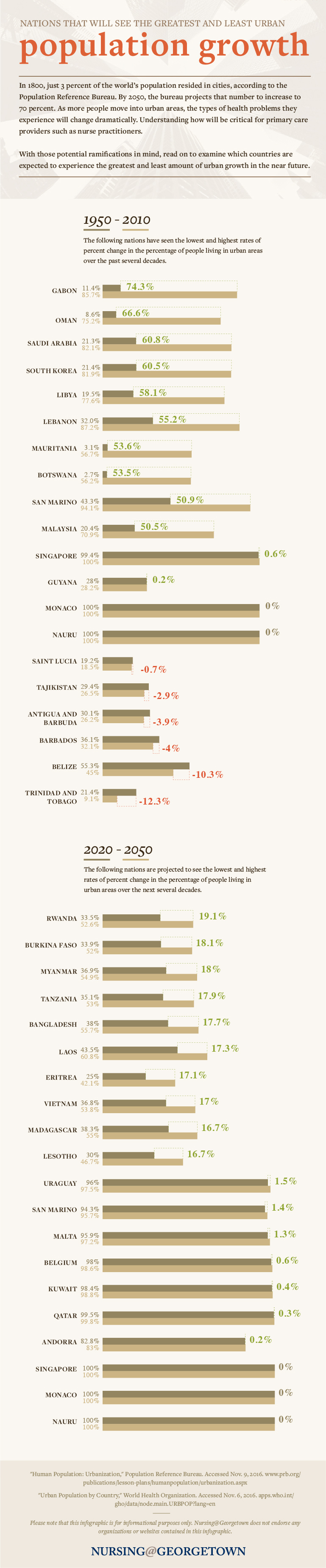

A recent study shows that more people than ever are relocating from their rural communities to live in urban areas. In 1800, just 3 percent of the world’s population resided in cities, according to the Population Reference Bureau. By 2050, the bureau projects that number will increase to a staggering 70 percent. The trend of city migration comes with unique challenges for primary care practitioners who are charged with maintaining the health of a growing population. Using findings from the World Health Organization (WHO), Nursing@Georgetown created the following graphic to show which nations are experiencing the most dramatic shifts in population density.

View the text-only version of this infographic.

Will Doig, of nonprofit Next City, writes that “the transformations wrought by global urbanization are many. Poverty is falling. Pollution is rising. The developing world is flexing its muscles.” When rapid urbanization happens it is largely unplanned, leading to slums, air pollution, poor sanitation, respiratory issues, and a higher rate of accidents and injuries. WHO reports that urban living tends to discourage physical activity and promote unhealthy food consumption as a result of overcrowding and reliance on motor vehicles.

These factors, in turn, contribute to a trend in the types of illnesses that threaten our livelihood. As Doig writes, “One of the biggest changes caused by the great migration to urban areas is one you rarely think about: The dramatic shift in how we get sick.” While infectious diseases have historically posed the highest risk, urbanization has driven a sharp increase in diabetes, asthma, cancer, and high blood pressure.

Ensuring that urban populations have equitable access to high-quality primary care is the key to managing chronic, noncommunicable diseases, as well as infectious diseases. Yet as city centers become more populated, barriers develop that prevent people from getting care. As the number of city inhabitants skyrockets, health care facilities are no longer equipped to keep up with demand.

Take the city of Dhaka in Bangladesh: According to 2011 data, there is one doctor for every 3,200 residents. The 3.4 million people who reside in the Dhaka’s slums fare the worst of all. The infant mortality rate in slums is 95 per 1,000 births — much higher than the urban average of 53 per 1,000 births and well above Bangladesh’s rural infant mortality rate of 66 per 1,000 births.[1]

Surviving infancy is no guarantee of a healthy childhood, as nearly 60 percent of children in slums are malnourished. As a result, research estimates an average of 30 percent to 45 percent of the total slum population struggles with sickness.

Access to quality care in urban areas also differs. People who are undocumented immigrants, homeless, or engaging in risky behaviors are especially vulnerable. Many people who live in poverty are unable to take time off work to visit a Family Nurse Practitioner (FNP) or other primary care provider. Crowded cities also become breeding grounds for epidemics like Ebola and Zika.

“The most transformative effect of crowds lies in the way they allow pathogens to become more deadly,” writes Sonia Shah of The Atlantic. “Pathogens that spread through social contact … are usually destined to be relatively mild. But crowds allow even these pathogens to become killers.”

As rapid urbanization continues, related health problems will likewise accelerate. That is why it is critical to integrate health considerations into urban planning and policymaking, says Myriam Vuckovic, PhD, assistant professor of international health at Georgetown University School of Nursing & Health Studies. As communities demand practical solutions to quell issues initiated by the spike of new residents, Vuckovic notes that government-built infrastructure has the potential to promote safe and healthy living. In addition, governments can invest in human capital and services, especially for the poor.

While metropolitan areas offer opportunities for employment, recreation, and culture, city dwellers also face unique health hazards. Nurse practitioners who plan to work in highly complex and dynamic urban environments should have an in-depth understanding of such risks. By learning to prioritize care and interventions for urban patients, nurse practitioners can help reduce health inequities in cities.

Please note that this blog post is for informational purposes only. Individuals should consult their health care professionals before following any of the information provided. Nursing@Georgetown does not endorse any organizations or websites contained in this post.

[1] (UNICEF 2010) Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey