Bringing Clinicians to Patients: How Nurses Are Closing the Rural Care Gap

In 35 of Texas’ 254 counties, residents who need medical attention have sparse, if any, health care provider options. Approximately 5.75 million Texans may be without essential primary care and according to the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Texas has met only 54 percent of its primary care needs. In Maine, that number is 36.8 percent. Puerto Rico is devastatingly underserved by primary care, with only 1.9 percent of needs met. These regions are symptomatic of the majority of states currently experiencing a shortage of licensed health care providers.

For the 58 million Americans residing in underserved parts of the country, available clinicians are largely Family Nurse Practitioners (FNP) and Certified Nurse-Midwives (CNM). These Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRN) have a graduate or doctoral education and are licensed to diagnose and treat patients as well as prescribe medication.

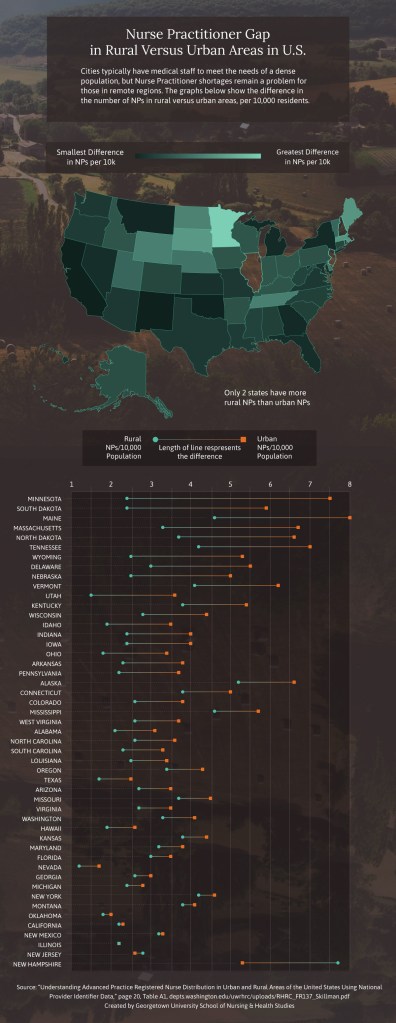

Cities typically have medical staff to meet the needs of a dense population, but Nurse Practitioner shortages remain a problem for those in remote regions. This graphs shows the difference in the number of NPs in rural versus urban areas, per 10,000 residents.

View a table of the per capita supply and number of Nurse Practitioners, by state.

Defining the Challenges of a Care Shortage

Georgetown University School of Nursing & Health Studies faculty member Victoria Dobbins, DNP, FNP-C, became an APRN after seeing the health care needs in her hometown of Clay County, West Virginia. Dobbins worked in public health at the time, and she realized nurses could do a lot to close health care gaps that exist in rural areas.

“If you are in an area [where] there’s no public transportation, you have limited resources, and the closest pediatrician is an hour and a half away, that makes it challenging,” she said.

Clay County is particularly short on resources for children and pregnant women, and Dobbins has been working to establish clinics in county schools that serve local families. She has helped ensure that clinics are staffed by Advanced Practice Nurses and that they employ nurses as care managers who provide screenings and help keep the community up-to-date on immunizations.

Dobbins has also contracted with a team of obstetricians who regularly drive 90 minutes into the county’s more isolated areas to hold clinics. She works alongside the obstetricians to establish rapport with patients and help manage their prenatal care.

According to Dobbins, FNPs and CNMs are a perfect fit for this challenging role, thanks to the nursing foundation in holistic care.

Meeting Rural Challenges with Whole-Person Care

“We look at ways to see the whole patient,” Dobbins said. “Why is that patient not taking the medication? Is it affordable? Is it a transportation issue? What resources can we provide?”

Dobbins recalled a patient with a persistent cellulitis who came into her office with tattered bandages.

“I asked if he was rewashing them, if he didn’t have the resources to get new ones,” she said. “He was, and he was doing the best he could, but he didn’t have running water. These are the kinds of challenges where Advanced Practice Nurses, with our process of thinking, really shine.”

Number of nurses in rural areas is on the rise, but is it enough?

In 2008,

APRNs constituted

17.6%

of rural primary care

In 2016,

APRNs constituted

25.2%

of rural primary care

While evidence shows that rural communities continue to be underserved by health care providers, new data suggests that a recent increase of Advanced Practice Registered Nurses in remote areas may be a solution to a dearth of providers.

Source: “Rural and Nonrural Primary Care Physician Practices Increasingly Rely on Nurse Practitioners.”

https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/pdf/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1158

Using Technology as a Tool

About two in five Americans living in rural areas do not have access to broadband Internet service; but 65 percent of rural residents own smartphones, which can be used to access a health care system.

Nevada, for example, is a largely rural state where technology is improving the ways Advanced Practice Nurses reach patients. APRNs in Las Vegas will connect to patients via telehealth providers, who provide primary care for non-urgent health problems, using a cellphone app. A video feed allows them to speak face-to-face with the APRN on the other end of the line.

The 24-hour system is designed to handle low-acuity patients quickly and without requiring a long drive into town. APRNs do see the occasional emergent condition, such as chest pain or slurred speech, for which they call 911 and stay with the patient until emergency responders have arrived.

In this way, nurses help people who may not otherwise receive the care they need.

Thriving as Rural Providers

First-line clinicians serve rural populations with a common shared philosophy: When it comes to health care, rural patients have less access, so clinicians do more.

“As Advanced Practice Nurses, we can make a lot of changes,” Dobbins said. “It energizes you to do what you got into nursing for in the first place and truly make a difference.”’

Citation for this content: Nursing@Georgetown, the online MSN program from the School of Nursing & Health Studies

Per Capita Supply and Number of Nurse Practitioners by State, 2010 NPI Data

| State | Urban NPs/10,000 Population | Rural NPs/10,000 Population | Difference in NPs/10,000 Population |

|---|---|---|---|

Minnesota | 7.5 | 2.4 | 5.1 |

South Dakota | 5.9 | 2.4 | 3.5 |

Maine | 8 | 4.6 | 3.4 |

Massachusetts | 6.7 | 3.3 | 3.4 |

North Dakota | 6.6 | 3.7 | 2.9 |

Tennessee | 7 | 4.2 | 2.8 |

Wyoming | 5.3 | 2.5 | 2.8 |

Delaware | 5.5 | 3 | 2.5 |

Nebraska | 5 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

Vermont | 6.2 | 4.1 | 2.1 |

Utah | 3.6 | 1.5 | 2.1 |

Kentucky | 5.4 | 3.8 | 1.6 |

Wisconsin | 4.4 | 2.8 | 1.6 |

Idaho | 3.5 | 1.9 | 1.6 |

Indiana | 4 | 2.4 | 1.6 |

Iowa | 4 | 2.4 | 1.6 |

Ohio | 3.4 | 1.8 | 1.6 |

Arkansas | 3.8 | 2.3 | 1.5 |

Pennsylvania | 3.7 | 2.2 | 1.5 |

Alaska | 6.6 | 5.2 | 1.4 |

Connecticut | 5 | 3.8 | 1.2 |

Colorado | 3.8 | 2.6 | 1.2 |

Mississippi | 5.7 | 4.6 | 1.1 |

West Virginia | 3.7 | 2.6 | 1.1 |

Alabama | 3.1 | 2.1 | 1 |

North Carolina | 3.6 | 2.6 | 1 |

South Carolina | 3.3 | 2.3 | 1 |

Louisiana | 3.4 | 2.5 | 0.9 |

Oregon | 4.3 | 3.4 | 0.9 |

Texas | 2.5 | 1. | 0.8 |

Arizona | 3.5 | 2.7 | 0.8 |

Missouri | 4.5 | 3.7 | 0.8 |

Virginia | 3.5 | 2.7 | 0.8 |

Washington | 4.1 | 3.3 | 0.8 |

Hawaii | 2.6 | 1.9 | 0.7 |

Kansas | 4.4 | 3.8 | 0.6 |

Maryland | 3.8 | 3.2 | 0.6 |

Florida | 3.5 | 3 | 0.5 |

Nevada | 1.7 | 1.2 | 0.5 |

Georgia | 3 | 2.6 | 0.4 |

Michigan | 2.8 | 2.4 | 0.4 |

New York | 4.6 | 4.2 | 0.4 |

Montana | 4.1 | 3.8 | 0.3 |

Oklahoma | 2 | 1.8 | 0.2 |

California | 2.3 | 2.2 | 0.1 |

New Mexico | 3.3 | 3.2 | 0.1 |

Illinois | 2.2 | 2.2 | 0 |

New Jersey | 2.6 | 2.8 | -0.2 |

New Hampshire | 5.3 | 7.7 | -2.4 |

D.C. | 8.7 | N/A | N/A |

Rhode Island | 4 | N/A | N/A |

National | 3.6 | 2.8 | 1.279591837 |

Source: “Understanding Advanced Practice Registered Nurse Distribution in Urban and Rural Areas of the United States Using National Provider Identifier Data (PDF, 3 MB),” page 20, Table A1