A Deeper Understanding of Palliative Care

According to a review published in the New England Journal of Medicine, seven in 10 Americans feel “‘not at all knowledgeable’” about the meaning of palliative care. What’s more, health care providers often refer to palliative care and end-of-life care synonymously, which can lead to more confusion.

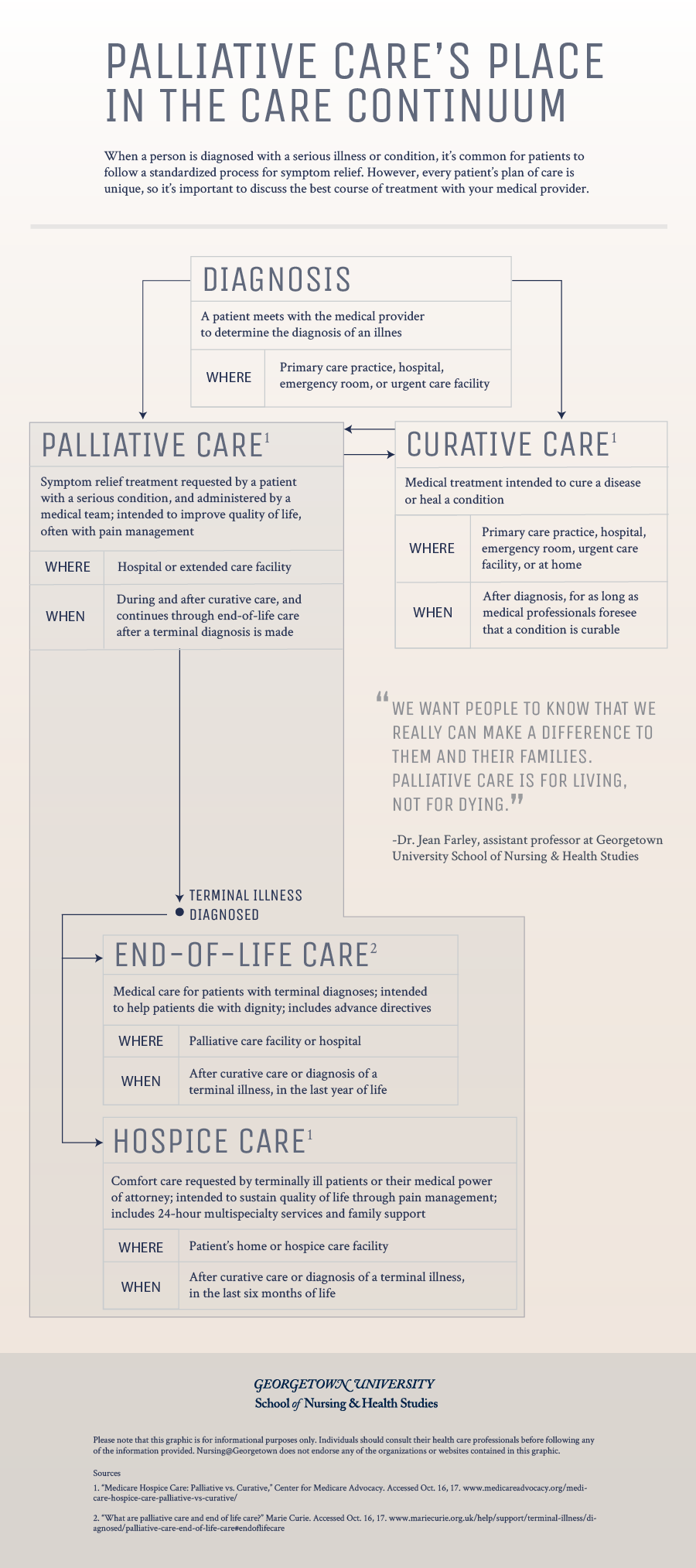

Palliative care, end-of-life care, and hospice care share a common goal: to relieve suffering. But there are also important distinctions.

According to the World Health Organization, palliative care is “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families … through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual.”

Jean Farley, DNP, RN, PNP-BC, assistant professor at Georgetown University School of Nursing & Health Studies, encourages people to think of palliative care as an umbrella term that includes pain management, hospice, and end-of-life care.

“Think of palliative care as a value-added layer to typical care for an individual experiencing a serious or life-limiting illness,” like cerebral palsy or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Farley said, “especially when that illness carries a heavy symptom burden that will persist over time.”

When patients are hospitalized for pain management and symptom relief, their families take in a lot of information from multiple points of contact, so it is critical to prioritize patient education during treatment. The infographic below illustrates how providers can explain the differences between curative, palliative, and end-of-life care to patients and their families.

View the text-only version of this graphic.

Quality of Life

Palliative services are typically provided by a team of interdisciplinary providers, including physicians, nurses, counselors, social workers, and chaplains. The team works together to assess and develop treatment plans with the patient and family that can provide the best possible quality of life.

“We’re in the business of making wishes come true,” said Farley, who coordinates the palliative care team at the HSC Pediatric Center in Washington, D.C. “Fewer distressing symptoms and an improved quality of life allows you to better engage in your life roles and build meaningful memories.”

Symptom Relief

Pain management is at the heart of palliative care. The medical team uses counseling, pharmacologic, non-pharmacologic, and alternative methods to treat pain and reduce other symptoms that may arise in a serious illness.

Transitional Care

In cases where a patient’s condition cannot be cured, the medical team assists patients moving from curative care to comfort care. The team consults with the patient, family members, and other care teams involved in the patient’s treatment to develop the best course of action. Together, all parties develop goals for treatment, which can include prolonging life, optimizing comfort, and preparing a patient and family for end-of-life care.

Cultural Considerations

Spiritual and religious values can inform a family’s priorities for health care treatment, so Nurse Practitioners must take cultural practices into consideration when developing a treatment plan. That involves learning about preferred methods of treatment from patients and their families with respect, appreciation, and sensitivity, and coming to mutual agreements about goals for care.

Early Exposure

Palliative care is most often introduced when curative care measures are stopped, but that disruption can make it difficult for patients and families to perceive palliative services as a positive transition.

“When the palliative care team isn’t called in until the eleventh hour, it’s unsettling for the patient and their family,” said Farley. She said the key to optimizing the outcomes of palliative care is involving the care team earlier in the patient’s diagnostic process.

Even if the team isn’t heavily involved from the beginning, establishing trust and commitment to the patient and family can make a difference if curative care comes to an end. Farley said the sooner patients, families, and curative care providers can get to know the team, the better.

Navigating Challenges

While end-of-life care can lead to disputes over goals for patient outcomes, common disputes in palliative care center around prognostic awareness — the ability to internalize the realities of a patient’s likely course of a condition or illness — especially in pediatric populations. The medical team and the patient’s family often come to the same conclusion about a child’s prognosis, but at a different pace.

“Parents want to feel that they exhausted every possible opportunity to help their child,” Farley said. Understandably, parents continue to hope for change, while providers often come to terms with the next steps for a patient’s care much sooner.

Conflict occurs when people feel as if they haven’t been heard, so providers should spend time consulting with families and listening to their concerns. Organizing cultural ceremonies or working with organizations like Make-a-Wish and Project Linus can help pediatric patients and their parents feel supported by the team.

“We want people to know that we really can make a difference to them and their families,” Farley said. “Palliative care is for living, not for dying.”

Citation for this content: Nursing@Georgetown’s Online FNP Program