How Does Race Impact Childbirth Outcomes?

The ability to protect the health of mothers and their infants during childbirth is a measure of a society’s development. Yet, even though North America is the richest region on the planet, the United States has one of the highest rates of maternal mortality in the developed world.

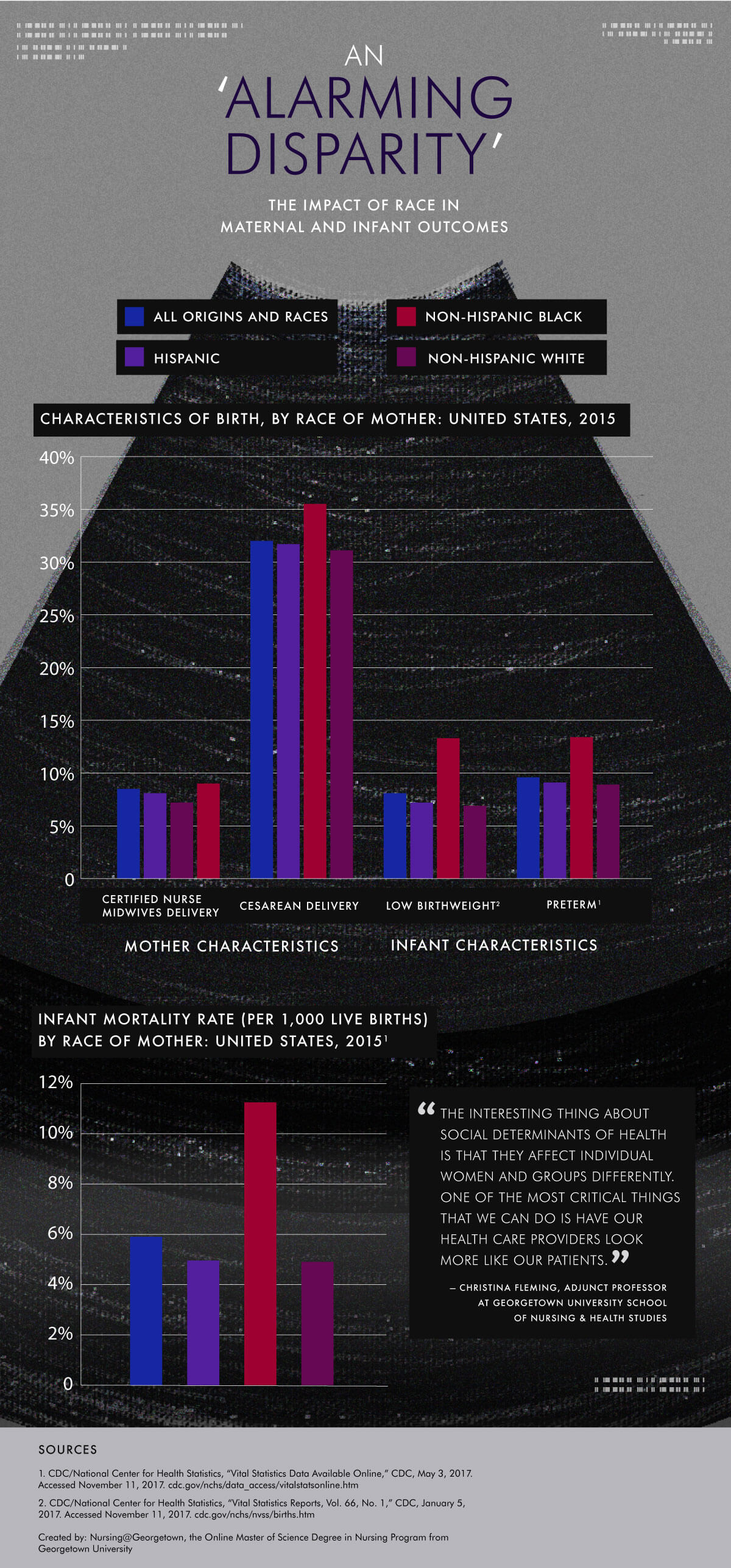

According to a 2014 Center for Reproductive Rights report, a woman living in sub-Saharan Africa has an equal or better chance of surviving childbirth than a black woman living in certain parts of Mississippi. Six in 10 maternal deaths in the United States are preventable, and because of the country’s racial disparities, maternal mortality is significantly more common among African-Americans. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), black women in American die at a rate of 43.3 per 100,000 live births, compared to only 12.7 deaths per 100,000 live births for white women.

Experts believe persistent poverty, chronic stress, and lack of access to health care providers are some of the factors that explain the problem. Interventions targeting social determinants of health (SDOH) may improve health equity.

Read the text-only version of this infographic.

Social determinants of health are the social, economic, and environmental conditions that affect physical and psychological outcomes. These complex social structures and economic systems impact health disparities in subtle and often overwhelming ways that are not easily addressed.

“The interesting thing about social determinants of health is that they affect individual women and groups of women differently,” said Georgetown University School of Nursing & Health Studies adjunct professor Christina Marea, MA, MSN, RN, CNM.

Marea said when she worked in a clinic for undocumented immigrants, she noticed many women’s complaints weren’t specific. When she drilled down for details, she found a wealth of factors.

Their issues, she said, “had a lot to do with their social, physical, and relationship environments, the deep insecurity of being undocumented immigrants, an inability to access the healthy traditional foods, increasing rates of diabetes and high blood pressure, and the complex pregnancies that accompany those disorders.”

An ‘Alarming Disparity,’ Unchanged

Mothers aren’t the only ones exposed to risk from racial and ethnic disparities. In 2015, black infants died at a rate of more than two times the rate for white infants, according to the CDC report.

Infant mortality is a measure of the general health of a society. Debora Dole, PhD, MSN, an associate professor and vice chair of the Department of Advanced Nursing Practice at the School of Nursing & Health Studies, found that a child born in the United States is more likely to die before his or her first birthday than in any other developed country.

The majority of infant deaths are due to causes such as prematurity, low birth weight, and congenital anomalies, according to Dole’s research.

“The alarming disparity in infant mortality has remained unchanged despite national and local efforts to develop program interventions that focus on parenting deficits,” she wrote.

Race plays a crucial factor when it comes to premature births. Black women give birth to preterm infants at a rate of more than two times the rate for white women, according to CDC data.

There are a number of ways a woman can reduce the risk of a preterm baby — preconception checkups to ensure a woman is in the best health possible, early prenatal care, management of medical problems, and healthy habits such as avoiding stress and eating properly.

Dole also suggests “community health professionals, in partnership with African-American communities, can build on [cultural] strengths to develop useful and relevant strategies that support adolescent mothers and their infants in an effort to reduce the disparity in infant mortality.”

The Role of Chronic Toxic Stress

Even when controlling for risk factors such as income, education, and alcohol and tobacco use, African-American women across the socioeconomic spectrum are subject to higher-risk pregnancies compared to their white counterparts, according to a report by the Midwives Alliance of North America. The report also found this gap increases as the socioeconomic spectrum narrows. A documentary produced by Fusion discovered black women who attended college experienced worse health outcomes than white women with no high school education.

To understand this discrepancy, researchers began looking for other factors that may account for these inequities. They found evidence that over time, microaggressions shown toward minorities rise to a level of stress that is chronic for mothers.

“Toxic stress is really just the accumulation of microaggressions, where people consistently are treating you as threatening, or undermining your accomplishments, or diminishing your contributions,” Marea said, “combined with other structural types of bias, like redlining — a form of discrimination in terms of housing access, the ability to buy housing, or the ability to obtain home loans.”

Such habitual microaggressions negatively affect the body, sending it into a chronic stress mode — a key risk factor for early labor and other poor birth outcomes, including low birth weight infants, according to the Midwives Alliance of North America.

Diversity as a Solution

When the health disparities among black women are not as simple as early prenatal care, the solution can seem complex and daunting. Research experts recommend recognizing black women as part of the solution, including more representation in the nursing field, which can help improve health equity.

While more research is being conducted on the best way to utilize minority nurses to effectively reduce disparities, success stories already show the importance of cultural awareness in health care.

A movement of black midwives in major cities has started to work toward reducing maternal and infant mortality in the African-American community.

A community health center in Massachusetts effectively utilized medical professionals and community workers from the same countries as the immigrant populations they serve. Infection rates have decreased in those patients since incorporating culturally competent care.

“One of the most critical things that we can do is have our health care providers look more like our patients,” Marea said. “What we see is that patients often respond better to providers who look more like them or who have shared life experiences. We’re missing out on all sorts of insights and ideas from health care providers of different backgrounds, who are Asian and Latino and African, African-American. We don’t even know what they would bring to designing better health care systems, better treatments, better interventions, and a better way to work with our populations.”

To have more providers of color, exposure must start early, Marea said. Encouraging high schoolers in Latino, African-American, and immigrant populations to work in the health care profession is likely to result in a diverse nurse and midwife demographic that looks more like the population they serve.

Research has shown that midwifery care, like the kind Marea and Dole provide, has been linked to positive birth outcomes, yet midwives attend less than 10 percent of births in the United States. Mothers who have used midwives are also more likely to breast-feed their infants. Although not well understood, breast-feeding is often a protection against Sudden Infant Death Syndrome.

The United States has a long way to go in decreasing health disparities among minority mothers and their infants. Unlike other countries, maternal deaths in the United States are a private tragedy rather than a public health disaster. There is no easy solution, but understanding the underlying issue can result in more effective strategies, including culturally diversifying practitioners of nursing and midwifery.

“When you think about what nurses can do,” Marea said, “we can intervene at the patient level with education and also the national level by advocating to our legislators, which is really pretty amazing.”

Citation for this content: Nursing@Georgetown, the online women’s health nurse practitioner program from the School of Nursing & Health Studies